Info

This article serves as a foundational guide to the essential knowledge required before transitioning into security. Explore the topics below to gain new insights and strengthen your technical baseline.

There are two major components that make up a website:

- Front End (Client-Side): The interface and logic rendered within the browser.

- Back End (Server-Side): The server-side infrastructure that processes requests and returns responses.

Core Web Technologies

Websites are primarily built using:

- HTML: To structure the content and define the layout of the website.

- CSS: To style and format the website, ensuring a visually appealing user interface.

- JavaScript: To implement complex features and interactive functionality.

This part of the website enables powerful functionality; with JavaScript, you can handle more complex operations than ever before, such as:

- Client-side routing and navigation logic.

- Request and Response handling via Fetch or Axios APIs.

- Dynamic animations and complex business logic.

- Advanced state management for sophisticated applications.

Warning

While

JavaScriptis incredibly powerful, improper implementation can lead to adverse results, including:

- Security Vulnerabilities: Such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS).

- Sensitive Data Exposure: Accidental leaking of keys or PII in client-side code.

- Performance Bottlenecks: Memory leaks or blocking the main thread.

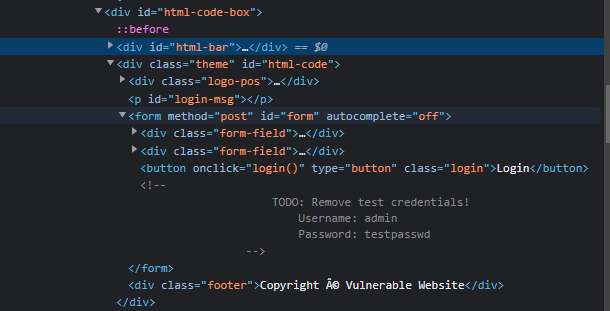

Sensitive Data Exposure

- Sensitive Data Exposure occurs when a web application fails to properly protect or sanitize sensitive information in clear-text, making it accessible to the end-user. This is frequently discovered within the application’s frontend source code.

- Exploitation: Attackers can leverage this sensitive information to escalate their access across different layers of the web application. For instance, developers might leave temporary credentials within HTML comments; if discovered in the page source, these credentials could be used to compromise user accounts or, in more severe cases, gain unauthorized access to backend infrastructure and internal components.

HTML Injection

- HTML Injection is a vulnerability that occurs when unsanitized user input is rendered directly on a web page. If a website fails to perform input sanitization—the process of filtering or encoding potentially malicious characters—an attacker can inject arbitrary HTML code into the application’s document structure.

- Input Sanitization is a critical security control, as user-provided data is frequently utilized in both frontend logic and backend processing. While other vulnerabilities like Database Injection (SQLi) involve manipulating server-side queries to bypass authentication, HTML Injection is primarily a client-side vulnerability focused on the presentation layer.

- Impact: When a user gains control over how their input is rendered, they can inject HTML or JavaScript. The browser executes this code as if it were part of the original source, allowing an attacker to alter the page’s appearance, capture user data, or hijack session functionality.

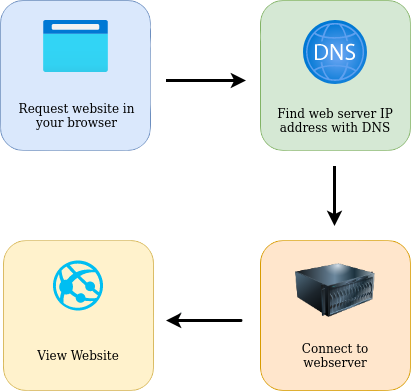

The real website in the internet

Abstract

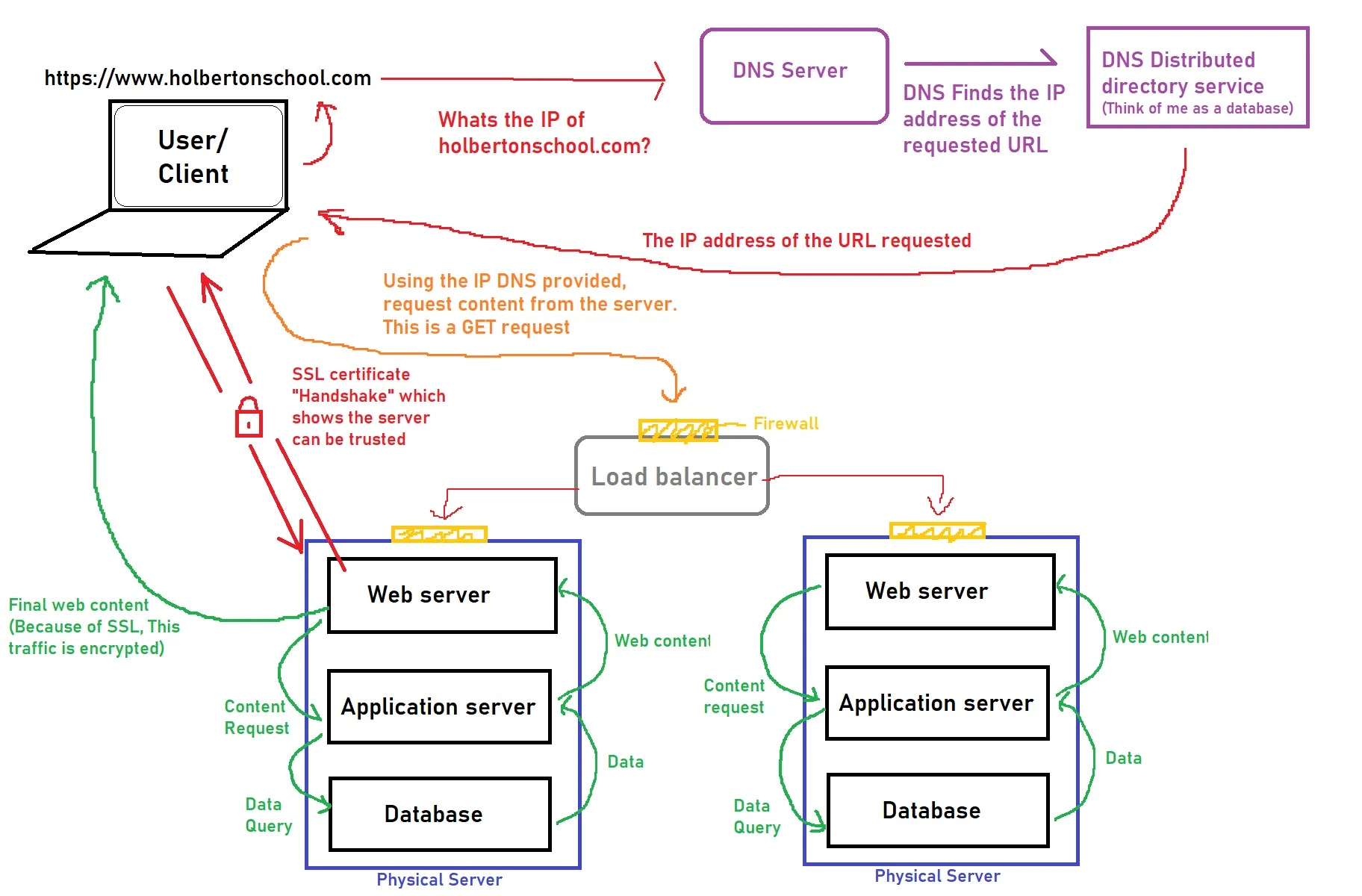

In summary, when you request a website, your computer must first resolve the server’s IP address through the DNS (Domain Name System). Once identified, your computer establishes a connection with the web server using the HTTP/HTTPS protocol. The server then transmits the necessary assets—such as HTML, JavaScript, CSS, and images—which your browser parses and renders to display the website correctly.

Load Balancers

- Load balancers provide two primary features: scalability, ensuring high traffic volumes are handled by distributing the load, and high availability, providing automated failover if a server becomes unresponsive.

- When requesting a website configured with a load balancer, the balancer acts as the entry point, receiving the incoming request first before forwarding it to one of the backend servers in the pool.

- The load balancer utilizes specific scheduling algorithms to determine the optimal server for each request. Common examples include Round Robin, which distributes requests sequentially across all servers, and Least Connections (Weighted), which directs traffic to the server currently handling the fewest active requests.

- To maintain reliability, load balancers perform periodic health checks on each backend instance. If a server fails to respond correctly, the load balancer marks it as unhealthy and redirects traffic to functional nodes until the failing server passes its health checks again.

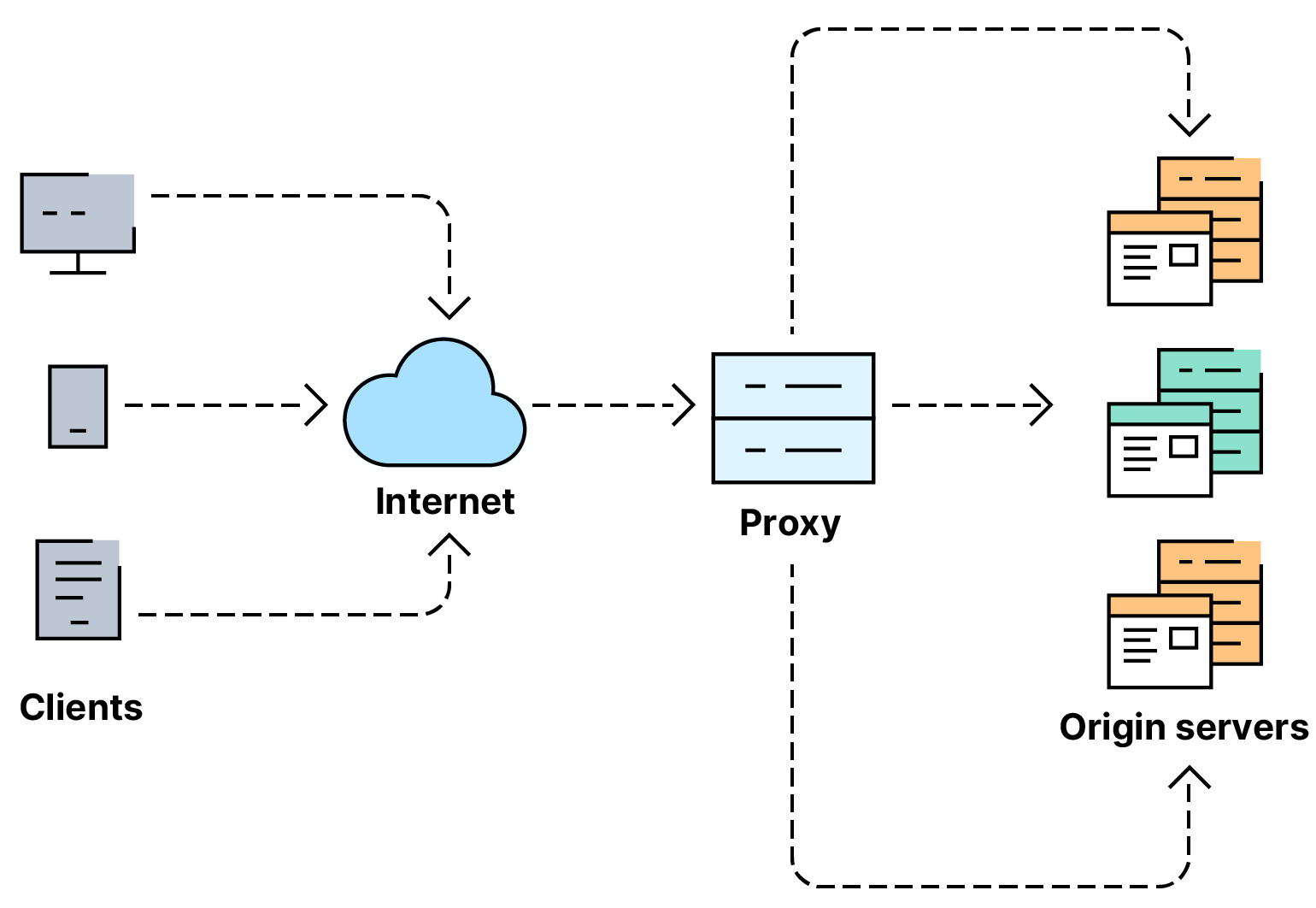

CDN (Content Delivery Networks)

- A CDN (Content Delivery Network) is a highly effective resource for reducing origin server load and mitigating high traffic. It enables the distribution of static assets—such as JavaScript, CSS, images, and video—across a global network of thousands of edge servers.

- When a client requests a cached file, the CDN utilizes geographic routing to direct the request to the nearest Point of Presence (PoP). This minimizes latency by serving content from a physically closer location rather than routing traffic to an origin server that may be on the other side of the world.

Databases

- Websites frequently require a persistent storage layer to manage user data. Web servers interact with databases to perform CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations, allowing data to be stored and retrieved dynamically.

- Database solutions scale from simple flat-text files to complex, distributed clusters designed for high performance and fault tolerance. Common database management systems (DBMS) include MySQL, MSSQL, PostgreSQL, MongoDB, and SQLite; each is optimized for specific use cases, such as relational data integrity or NoSQL flexibility.

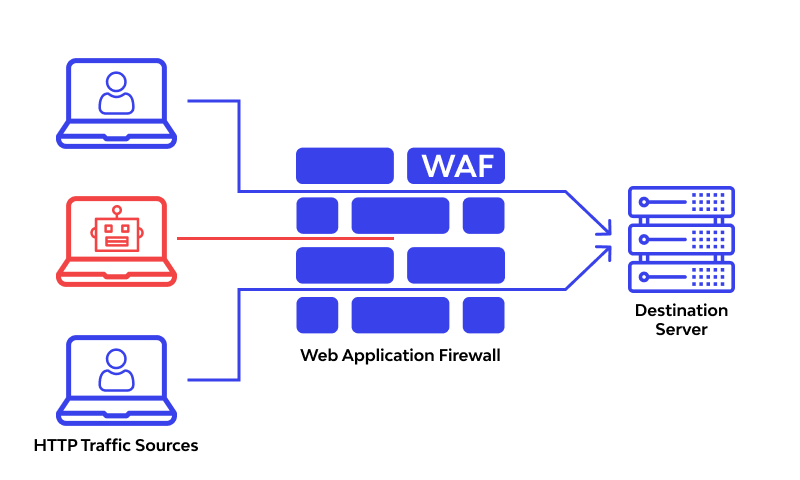

WAF (Web Application Firewall)

- A WAF (Web Application Firewall) sits inline between incoming web requests and the origin web server; its primary function is to shield the infrastructure from application-layer exploits and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks.

- It inspects incoming traffic for common attack vectors—such as SQL Injection (SQLi) and Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)—and employs bot mitigation techniques to distinguish between legitimate browser traffic and automated malicious scripts.

- The WAF also enforces rate limiting to prevent resource exhaustion, restricting the number of requests allowed from a single IP address within a specific timeframe. If a request matches a known attack signature or exceeds defined thresholds, it is dropped at the edge, ensuring malicious traffic never reaches the web server.

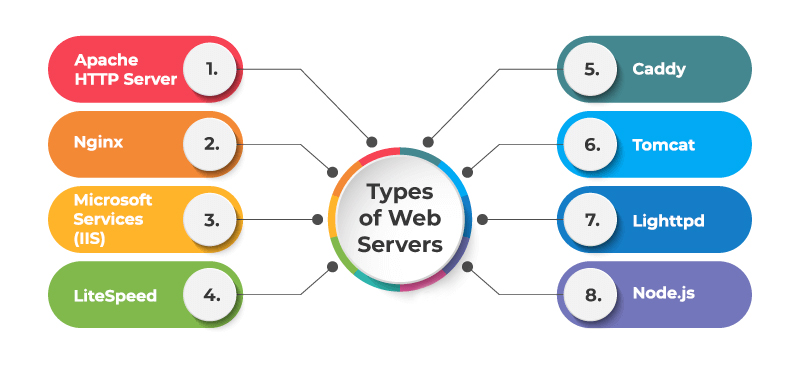

Web Servers

- A web server is a software application that listens for incoming network connections and utilizes the HTTP/HTTPS protocols to deliver web content to clients. Popular web server implementations include Nginx, Apache, IIS, and runtime environments like Node.js.

- Web servers serve assets from a designated document root, defined within the server configuration. On Linux-based systems, both Nginx and Apache typically default to

/var/www/html, whereas IIS on Windows systems defaults toC:\inetpub\wwwroot.

Virtual Hosts

- Web servers can host multiple independent websites with distinct domain names on a single instance by utilizing Virtual Hosts (often referred to as Server Blocks in Nginx).

- When a request arrives, the web server inspects the

Hostheader within the HTTP request. It matches this hostname against its configuration files—which are standard text-based directives—to determine which site to serve. If no specific match is found, the server routes the request to a designated default server or catch-all block. - Each Virtual Host can be mapped to a unique document root on the file system, allowing separate websites to maintain isolated directory structures on the same disk.

- There is no hard architectural limit to the number of websites a single web server can host; the capacity is primarily governed by the available hardware resources (CPU, RAM, and I/O).

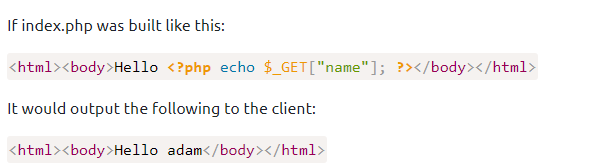

Static vs Dynamic Content

- The visual interface and elements you interact with directly in your browser are referred to as the Front-end.

- Content is categorized into two types: Static Content, which remains constant for every user, and Dynamic Content, which changes based on user interaction or data processing.

- These dynamic changes are processed on the Back-end, where programming and scripting languages execute logic “behind the scenes.” This processing is invisible to the end user but determines the final output rendered in the browser.

Backend

- The Server acts as the delivery hub, receiving requests from the browser and sending back the necessary files and data to display the website.

- Information like user profiles, posts, and settings are kept in the Database, a structured storage system that the backend “queries” to retrieve or save data.

- Connecting these parts is the API (Application Programming Interface), which serves as a messenger, allowing the frontend and backend to communicate and share data securely.

- Authentication and Security protocols run on the backend to verify user identities and protect sensitive information before it ever reaches the user’s screen.

Web Protocol (HTTP/HTTPS)

Info

This kind is important things in the internet, the critical part which cause the fail or succeed of website, performance, dns, caching and more thing which essential did it

What is HTTP(S)?

- HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the foundational protocol for viewing websites, developed by Tim Berners-Lee and his team between 1989 and 1991. It defines the standard set of rules for transmitting web data—including HTML, images, and videos—between a client and a web server.

- HTTPS (Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure) is the encrypted version of HTTP. It utilizes TLS/SSL certificates to encrypt data in transit, protecting it from eavesdropping and tampering. Furthermore, HTTPS provides identity verification, ensuring that the client is communicating with the legitimate web server rather than an impersonator.

- To implement HTTPS, a website requires an SSL/TLS Certificate issued by a Certificate Authority (CA). This certificate facilitates the cryptographic handshake used to generate session keys and verify the site’s authenticity.

Request and Response

Question

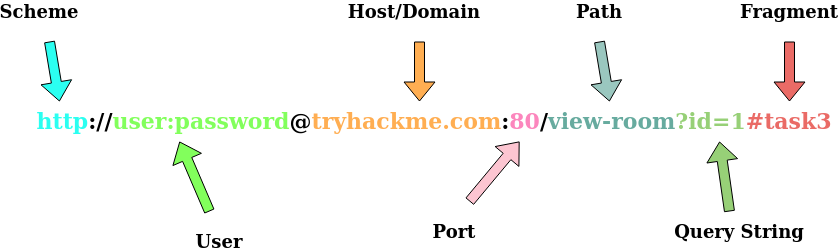

What is a URL? (Uniform Resource Locator)

Note

If you’ve used the internet, you’ve used a URL before. A URL is predominantly an instruction on how to access a resource on the internet. The below image shows what a URL looks like with all of its features (it does not use all features in every request).

- Scheme: Specifies the protocol used to access the resource, such as HTTP, HTTPS, or FTP (File Transfer Protocol).

- User:Password: Optional credentials for services requiring authentication; the username and password can be embedded directly within the URL.

- Host: The domain name (FQDN) or IP address of the server hosting the resource.

- Port: The specific communication endpoint on the server. While commonly 80 for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS, it can be any value within the range of 1–65535.

- Path: The specific location or file path on the server where the resource resides.

- Query String: A set of key-value pairs providing additional parameters to the requested path (e.g.,

/blog?id=1requests a specific resource identified by the ID). - Fragment: An internal page reference (anchor) that points to a specific section within the resource. This allows the browser to scroll directly to a designated location upon loading.

Making a request

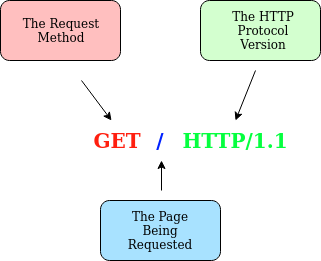

Example Request:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: tryhackme.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Firefox/87.0

Referer: https://tryhackme.com/- Line 1: Specifies the

GETmethod (covered in the HTTP Methods section), requests the root directory (/), and indicates the use of theHTTP/1.1protocol. - Line 2: The

Hostheader specifies the target domain astryhackme.com. - Line 3: The

User-Agentheader identifies the client browser asFirefox version 87. - Line 4: The

Refererheader indicates that the previous page directing us here washttps://tryhackme.com. - Line 5: An HTTP request concludes with an empty line (CLRF), signaling to the web server that the transmission is complete.

For a deeper dive into request parameters, refer to the official documentation on HTTP Headers.

Example Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.15.8

Date: Fri, 09 Apr 2021 13:34:03 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 98

<html>

<head>

<title>TryHackMe</title>

</head>

<body>

Welcome To TryHackMe.com

</body>

</html>To break down each line of the HTTP response:

- Line 1: Indicates the protocol version (

HTTP/1.1) followed by the HTTP Status Code (in this case,200 OK), which confirms the request was processed successfully. - Line 2: The

Serverheader identifies the software and version number powering the web server. - Line 3: The

Dateheader provides the current timestamp and timezone of the server at the time of the response. - Line 4: The

Content-Typeheader informs the client of the media type of the resource (e.g.,text/html,image/png,application/json), ensuring the browser renders the data correctly. - Line 5: The

Content-Lengthheader specifies the size of the response body in bytes, allowing the client to verify that the entire payload was received. - Line 6: Similar to the request, the HTTP response includes a blank line (CRLF) to separate the headers from the message body.

- Lines 7–14: The Response Body, containing the actual data requested (e.g., the HTML source code for the homepage).

HTTP Method

The four primary HTTP methods used to build RESTful APIs (CRUD operations) are:

- GET (Read): Used to retrieve information or resources from a web server without modifying state.

- POST (Create): Used to submit data to the server, typically resulting in the creation of a new record or resource.

- PUT (Update): Used to send data to the server to update or replace an existing resource entirely.

- DELETE (Delete): Used to remove specific information or records from the web server.

Note

HTTP extends beyond these four methods to include others such as

PATCH(for partial updates),HEAD, andOPTIONS. For a comprehensive list, refer to the official HTTP documentation.

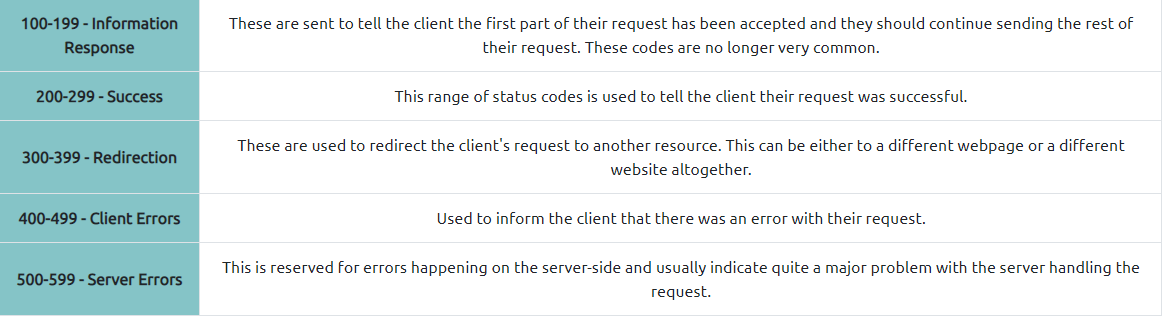

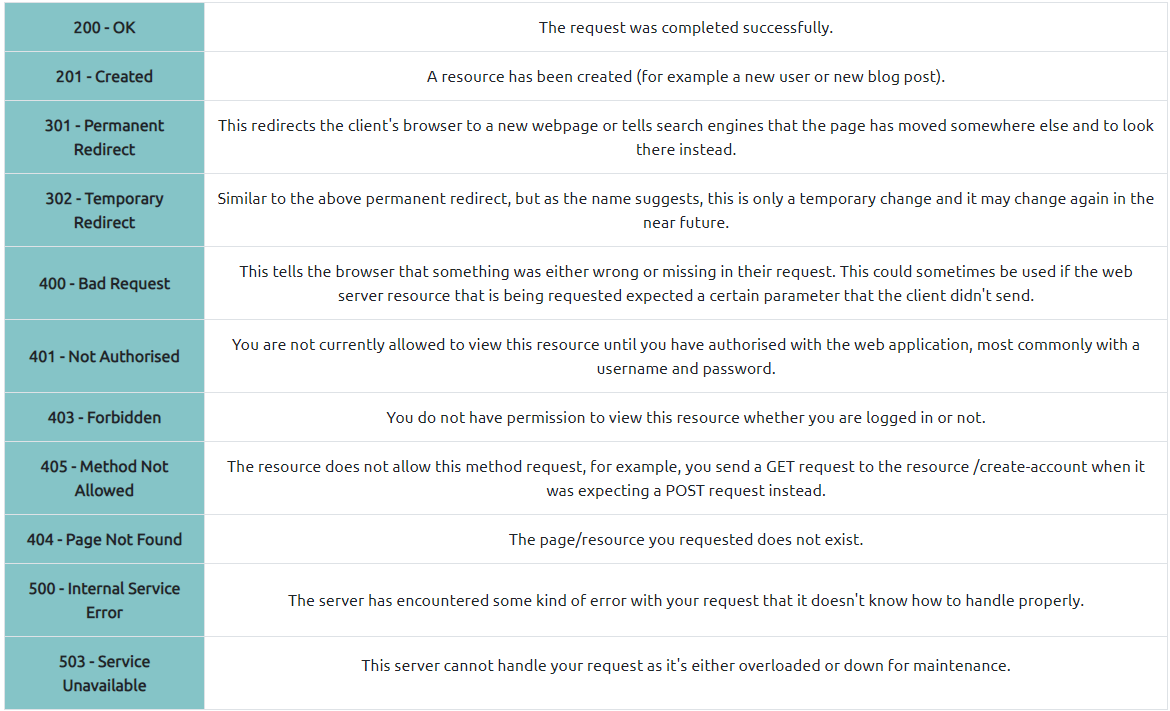

HTTP Status Codes

The first image is about range of a status code informing the client of the outcome of their request and also potentially how to handle it. These status codes can be broken down into 5 different ranges

Common HTTP Response Codes

DNS (Domain Name Server)

This below resource are refer with THM (TryHackMe)

- DNS (Domain Name System): Acts as the internet’s phonebook, providing a human-readable way to communicate with devices without needing to memorize complex numerical addresses.

- IP Address: Every device connected to the internet is assigned a unique identifier known as an IP address.

- Structure: A standard IPv4 address (e.g.,

104.26.10.229) consists of four octets, with each set of digits ranging from0to255, separated by periods. - Functionality: DNS translates domain names (like

google.com) into their corresponding IP addresses, allowing users to access websites using easy-to-remember names instead of raw numerical data.

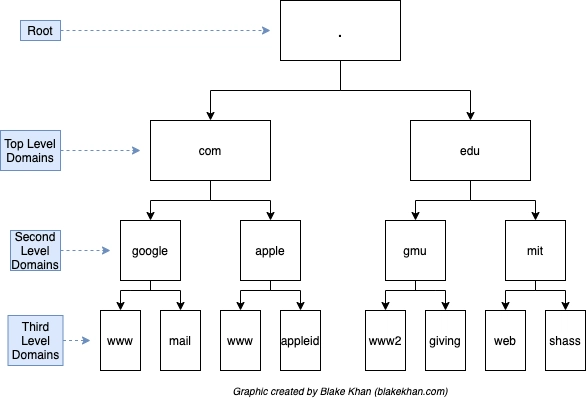

Domain Hierarchy

- TLD (Top-Level Domain): The TLD is the rightmost segment of a domain name (e.g.,

.com,.vn,.net). TLDs are categorized into two primary types:- gTLD (Generic Top-Level Domain): Indicates the purpose of the domain, such as

.comfor commercial or.orgfor organizations. - ccTLD (Country Code Top-Level Domain): Represents a specific geographical location or country, such as

.vnfor Vietnam. - You can view the full authoritative list of TLDs at the IANA database.

- gTLD (Generic Top-Level Domain): Indicates the purpose of the domain, such as

- Second-Level Domain (SLD): Using

tryhackme.comas an example,.comis the TLD, andtryhackmeis the SLD. When registering a domain, the SLD is limited to 63 characters (excluding the TLD) and may only contain alphanumeric characters (a-z,0-9) and hyphens. Hyphens cannot be placed at the beginning or end of the SLD, nor can they appear consecutively. - Subdomain: A subdomain is positioned to the left of the Second-Level Domain, separated by a period. For example, in

blog.tryhackme.com,blogacts as the subdomain. You can explore this further in the DNS in Detail lab.

Note

You can knowing the construct is

https://subdomain.second-level.TLD

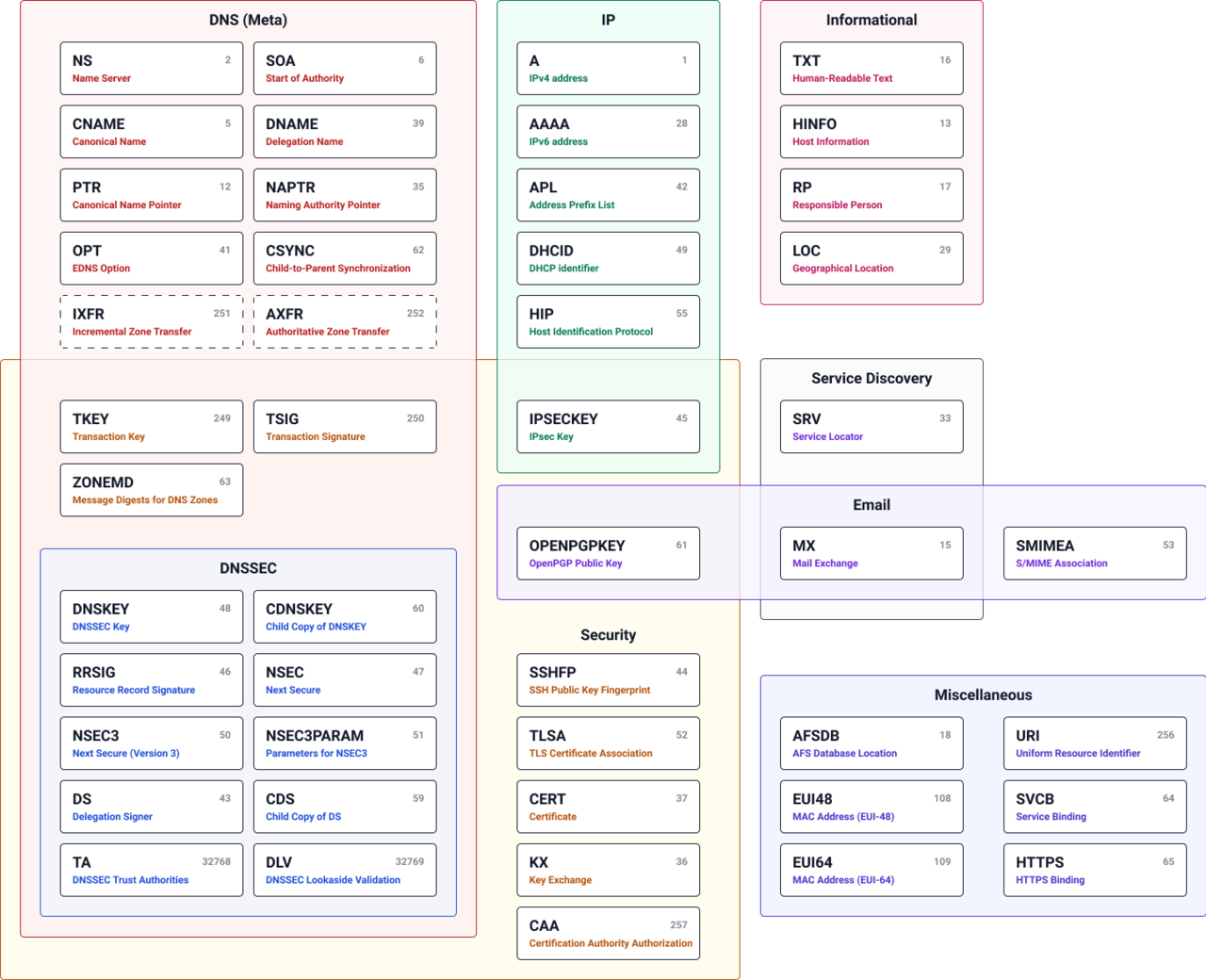

Record Types

- DNS serves more than just websites; it utilizes various record types to handle different networking tasks. Below are the most common DNS records encountered in DevOps and Systems Administration:

- A Record: Maps a domain name directly to an IPv4 address (e.g.,

104.26.10.229). - AAAA Record: Maps a domain name to an IPv6 address (e.g.,

2606:4700:20::681a:be5). - CNAME Record: (Canonical Name) Forwards a domain or subdomain to another domain name rather than an IP. For instance,

store.tryhackme.commight resolve toshops.shopify.com, triggering a subsequent lookup to find the final IP address. - MX Record: (Mail Exchanger) Directs email to the specific servers responsible for the domain’s mail delivery (e.g.,

alt1.aspmx.l.google.com). These records include a priority value, instructing mail servers on the preference order for delivery, which is essential for failover and redundancy. - TXT Record: A flexible text field used to store machine-readable data. Common use cases include SPF (Sender Policy Framework) to prevent email spoofing and domain ownership verification for third-party SaaS integrations.

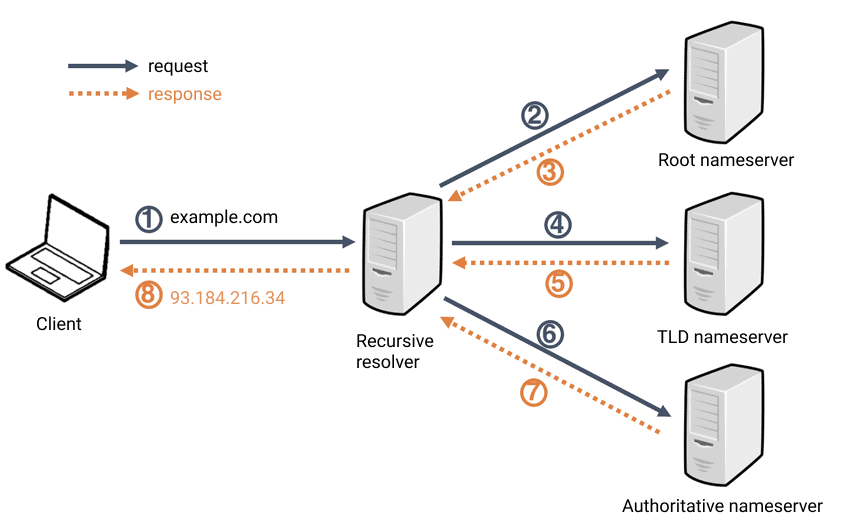

Making A Request

- Local Cache: When you request a domain, your operating system first inspects its local DNS cache for a recent entry. If no valid record is found, the request is forwarded to a Recursive DNS Resolver.

- Recursive DNS Resolver: Typically managed by your ISP or a public provider (like Cloudflare or Google), this server also maintains a cache. If the record exists there—common for high-traffic sites like Google or GitHub—it is returned immediately. If not, the resolver initiates a hierarchical lookup starting at the Root Nameservers.

- Root Nameservers: These serve as the internet’s DNS backbone. They do not hold specific IP addresses but instead direct the resolver to the appropriate Top-Level Domain (TLD) Server based on the extension (e.g.,

.com,.io,.net). - TLD Nameservers: The TLD server manages registry information for its specific suffix. It points the resolver toward the Authoritative Nameserver (often managed by a DNS provider like Route 53 or Cloudflare) responsible for the specific domain.

- Authoritative Nameserver: This is the final authority that holds the actual DNS records (A, CNAME, etc.). It provides the requested data back to the Recursive Resolver.

- TTL and Caching: Once the Recursive Resolver receives the record, it caches the result for a duration defined by the TTL (Time To Live)—a value in seconds. It then delivers the final answer to the client. This caching mechanism significantly reduces latency and network overhead for subsequent requests.

Cookies

- Data Storage: Cookies are small fragments of data stored locally on the client’s machine (the web browser).

- Initialization: A cookie is established when the web server includes a

Set-Cookieheader in its HTTP response. - State Management: Since HTTP is a stateless protocol—meaning it does not natively retain data between different request-response cycles—cookies serve as a persistence mechanism.

- Session Continuity: For every subsequent request, the browser automatically attaches the stored cookie data back to the server. This allows the server to recognize the user, maintain session states, persist personalized settings, or track user activity across the site.

Note

While cookies serve various functions, their primary use case is Web Authentication. Instead of storing sensitive credentials like passwords in plaintext, cookies typically store a Session Token—a unique, cryptographically secure identifier that is difficult to guess or forge.

You can easily inspect the cookies your browser transmits to a website using built-in Browser Developer Tools.

- Open Developer Tools: Open the tools and navigate to the Network tab.

- Capture Traffic: This tab logs every resource requested by your browser. Refresh the page to see the activity.

- Inspect Headers: Select a specific network request to view its detailed breakdown.

- View Cookies: If a cookie was included in the transaction, you can find the specific data under the Cookies sub-tab or within the Request Headers section.